Dogs Don’t Need Carbs?

By Dr. Mark Roberts, PhD

Do dogs really need carbohydrates as part of their diet? Let’s get straight to the point on this one, the answer in no. Indeed, neither the American Association of Feed Control Officials (AAFCO), The National Research Council (NRC) or the European Pet Food Industry (FEDIAF) have a requirement for carbohydrates. The key point here, is to understand that dogs need to maintain blood glucose within a normal range, but this doesn’t mean they need to consume carbohydrates, let me explain.

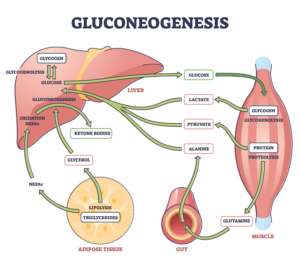

When dogs consume a diet high in fat and protein, with no carbohydrates, they use non carbohydrate (or the fancy word gluconeogenic) pathways to not only maintain blood glucose, but to also stop any of the spikes, typically seen in carbohydrate dense foods. Indeed, the word, gluconeogenesis, simply means gluco (glucose), neo (new) and genesis (creation).

Amino acids (which come from protein), more specifically alanine, glycine, and serine result in blood glucose being generated after first being broken down by certain enzymes in the liver. Amino acids serve several important jobs, including building and repairing tissues like hair, nails, bones, muscles, cartilage, and skin. Additionally, many enzymes and hormones are constructed from amino acids. So, regarding utilising amino acids as a source energy on a long-term basis, a high protein content is required, (so as not to risk negating the other roles amino acids need to perform). The alternative approach is to have a higher dietary percentage from fat, hence enabling dogs to use this alternative energy pathway.

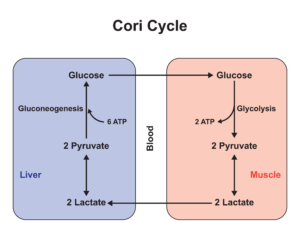

Another way in which glucose is made without carbohydrates involves something called the Cori cycle. In this process, lactate (which is produced as the body turns food into energy), collects in the muscle cells and is taken up by the liver. The liver then performs gluconeogenesis, essentially converting lactate back to glucose. The glucose then travels back to the muscles to be used.

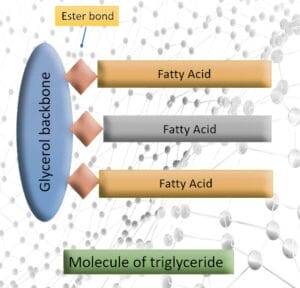

The final way we want to focus on how a dog makes glucose from non-carbohydrate sources involves a type of fat called triglycerides, found in both dietary fat and body composition. When triglycerides are broken down, the result is the release of fatty acids and glycerol. We shall discuss fatty acids in the future, however regarding glycerol, its contribution to glucose production (which occurs in the liver) is directly correlated to being released from the fatty acids I mentioned.

In my own research, I found that when dogs were strictly fed a high fat and protein based diet for 28 days, blood glucose concentrations were normal. In addition, last year I completed approximately 2000 miles of training with my dogs consuming a diet with essentially no more than 1% of energy derived from dietary carbohydrate. I regularly measured my dog blood glucose, with all values within range, additionally, no impaired performance or fatigue was observed.

In other research, two groups of dogs were fed either a high carbohydrate (HC) or high fat (HF) diet, while undergoing an aerobic exercise program using a treadmill1. On completion of the training phase, it is concluded that at the start there was an increased glycogen storage associated with the HC diet fed dogs, compared to the HF fed dogs. However, despite this, a much greater level of glycogen depletion occurred in the HC dogs, compared to the HF dogs. A simple way to understand this, is that glycogen is basically stored carbohydrate, (think of it as a fuel tank), hence why the HC group had a higher amount prior to the exercise component. Despite the HC dogs having fuller “fuel tanks,” because the HF dogs were much better at sparing carbohydrates during intense exercise, they were deemed to be a better dietary strategy for endurance. Essentially this means the HC dogs fuel tank, emptied much faster than the HF diets, even though this group had lower levels to start with.

Supporting this finding, another study found that using sled dogs, running 160 km (100 miles) a day, for 5 consecutive days did not develop cumulative glycogen depletion2. This was even more impressive given that the dogs consumed a relatively limited carbohydrate intake. As previously discussed, glycerol when separated from free fatty acids, results in stimulating glycogenolysis. However, interestingly, in that in conjunction with this gluconeogenic “switching on” a significant inhibition of the conversion of stored glycogen to glucose for use has been observed in dogs3. Reverting to the fuel tank analogy I used, this basically means the fuel tank (containing glycogen) has been turned off, and the use of other non-carbohydrate sources to synthesize glucose is turned on. However, to enable this process to occur, a limited amount of dietary carbohydrate must be consumed, otherwise a depletion in the fuel tank will occur and performance impaired. Indeed, the impact of this process, was elegantly highlighted in both the studies discussed.

The only remaining option to reduce fatigue in a working dog fed a high carbohydrate diet, is therefore to have them consume carbohydrate-based foods on a regular basis (approximately every two hours), or performance will be negatively impacted. This approach is common in human exercise nutrition, with the term “hitting the wall,” referring to when the fuel tank is empty, and glucose replenishment needed (gel packs, drinks etc.). The key difference when utilising fat as the source of fuel, is that not only does fat simply have much more energy than carbohydrate, but even a lean dog (or human), has a hugely greater amount of stored energy in fat, than carbohydrate. This means, the need to constantly “top up” energy stores on a frequent basis is not required.

In summary, dogs are easily capable of thriving on a diet, free of carbohydrate content. However, the need to provide quality animal proteins and fats is important for many nutritional reasons, including helping the pathways I discussed to operate optimally, in turn maintaining healthy blood glucose levels in the animal.

References

- Reynolds, A. J., Fuhrer, Laurent., Dunlap, H. L., Finke, Mark., & Kallfelz, F. A. (1995). Effect of diet and training on muscle glycogen storage and utilization in sled dogs. Journal of applied physiology, 79(5), 1601-1607.

- McKenzie, Erica., Holbrook, T., Williamson, Kathy., Royer, Christopher., Valberg, Stephanie., Hinchcliff, Ken., … & Davis, M. (2005). Recovery of muscle glycogen concentrations in sled dogs during prolonged exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 37(8), 1307-1312.

- Chu, C. A., Sherck, S. M., Igawa, K., Sindelar, D. K., Neal, D. W., Emshwiller, M., & Cherrington, A. D. (2002). Effects of free fatty acids on hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in conscious dogs. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 282(2), E402-E411.